Moses Mendelssohn was the first Jew to break the walls of the Orthodox ghetto and become a member of Berlin's intellectual elite. Throughout his life the so-called "Socrates of the Jews" walked a thin line between loyalty to his community and attraction to his enlightened friends. For that reason, he was accused of insulting both sides: "I am like the husband", so he said, "Whose wife accuses him of impotence while the maidservant accuses him of causing her pregnancy" (Feiner, Kindle Location 2893(.

A Boy in Berlin

Moshe Ben Menahem was born in Dessau, Germany, in 1729 to a middle-class family that was related, via the mother's side, to Moshe Isserles (The Rema) of Krakow.

A brilliant boy with a religious background like his was expected to follow a career in Torah studies and excel in it.

The most significant figure in his life was Rabbi David Frankel, who became his teacher when Mendelssohn was 11. When Rabbi Frenkel was appointed Rabbi of Berlin in 1743, the fourteen-year-old Moshe decided to abandon his parents' house and follow his teacher to the big city.

In his book "A German Requiem," the writer Amos Elon delineates the story of the golden age of German Jewry by focusing on two events. The book begins with the words: "In the autumn of 1743, a fourteen-year-old boy entered the city of Berlin at the gate ... the only one where Jews were allowed to enter (and cattle)." (Elon, p. 7): It ends with the flight of the philosopher Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) from Hitler's Berlin: "She also had a history of her own. She had lovers and friends and they disappointed her, a circle began to close, and the train galloped from Berlin in the opposite direction to that of the boy Moshe Mendelssohn, who had left two hundred years earlier, and was on his way to fame in enlightened Berlin." (Elon, p. 401)

Elon describes the boy as small for his age, frail and sickly. "A childhood of poverty has left him with skinny arms and legs, an annoying stutter and a hunched back ... and yet he had fine features, and under his arched forehead his eyes sparkled in deep expression alongside well-shaped lips, cheeks, nose and chin." (Elon, p. 7). After an arduous journey he arrived at the house of his Rabbi, who arranged his residence and living quarters free of charge. In those days he would go to the attic and secretly read books which were not taught at the yeshiva. Deviation from sacred studies was dangerous because the rabbinic establishment was able to order a deportation from the city, partly since the authorities, who wished to minimize Jewish residence permits, did not interfere with the Jews' internal considerations. In 1750, the yeshiva student was hired as a private tutor for the children of a wealthy industrialist who recognized Mendelssohn's extraordinary talents. He eventually appointed him as an official in a silk factory, and over the years the two men co-managed the factory. This work left Mendelssohn with enough free time for his intellectual pursuits and allowed him to maintain his intellectual independence by freeing him from the worries of earning a living.

His Way to Philosophy

In Ashkenazi-Jewish-religious culture, Maimonides' (The Rambam) teachings were shunned, primarily due to the fear that philosophical thought would harm religious faith. Only in 1742 was the "The Guide for the Perplexed" reprinted, and Mendelssohn was exposed to it during his early years in Berlin.

With his thirst for knowledge Mendelssohn was drawn to Maimonides' teachings, and even attributed the formation of the scoliosis in his back and his transformation into a hunchback to the many hours of reading he devoted to Maimonides' writings: ““He afflicted my flesh and I became feeble because of him,” his first Jewish biographer Isaac Euchel quoted him, “and yet I loved him greatly for he transformed many hours in my lifetime from sorrow into joy.” (Feiner, Kindle Locations 395).

The study of Maimonides' writings aroused his curiosity and desire to expand his education, and at that time he also met several young Berliners who dared to deviate from their holy studies without fearing the Rabbis. A friend who was a medical student taught him Latin, another friend confided in him the secrets of mathematics, and a third gave him a book by the philosopher John Locke, which he read with the aid of a dictionary. He studied Latin, German, French, Classical Greek and English to enrich his knowledge. The cultural and intellectual gaps he had to complete were enormous. He devoted his leisure time to the writings of Locke, Newton, the Greek classics, Leibniz, and Rousseau.

Mendelssohn was a bachelor who lived in an attic. The passions of a young man of his age were replaced with a passion for knowledge. He described the many hours he devoted to his studies in erotic terms - for example: “Mathematics, too, which is generally perceived as lacking sparkle, becomes a source of sublime pleasure: “The amazing multiplicity of aspects embodies in the most pleasing order of all turns even mathematics into an occupation that heightens ecstasy." “(Feiner, Kindle Locations 471).

"He later acknowledged that he never studied at a university, never listened to lectures at any academic college, achieving everything through diligence and his own efforts. With a satisfied retrospective glance, he pronounced himself a self-made man. From this standpoint Mendelssohn fulfilled the ideal of the Enlightenment: with his natural talents and intelligence a man can seize his own fate, escape the limitations into which he was born, and shape his own intellectual life (Feiner, Kindle Location 427).

Spinoza's writings fascinated him, but he internalized the lesson of the boycott imposed on the philosopher who crossed the boundaries of religious faith. Mendelssohn drew a clear dividing line between Maimonides' rational philosophy, which challenged many accepted religious beliefs, and Spinoza's philosophy which rebelled against the religious ethos. He sympathized with Spinoza, who lived a modest life dedicated to contemplation, but disapproved of his theory. He interpreted Spinoza's attitude toward religion as a "mistake" that occurred because the philosopher got lost in the maze of his own thoughts. Mendelssohn also had reservations about Voltaire, who despised religion in general. For Mendelssohn, life without religious faith is not a life but rather a slow death.

Mendelssohn and the Orthodoxy

Although Mendelssohn was careful to maintain an Orthodox and observant lifestyle, he became, in the eyes of the ultra-Orthodox, a mythic figure who represented all the "ills" of the Enlightenment. In "Mendelssohn and the Orthodox" (Note 1) Prof. Feiner explains: "To them he became a demonic historical figure possessed of destructive powers, with the responsibility for all the crises of the modern age: assimilation, the disintegration of the traditional community, loss of faith, religious permissiveness and weakening authority of the rabbinic elite. The main plot of which was a grand plot of a huge and malicious rebellion in tradition and rabbis. One of Mendelssohn's sworn enemies, Akiva Yosef Schlesinger, a disciple of the hatam Sofer, wrote of Mendelssohn: “The evil Moses of Dessau, the leader of the rebels who has the cunning of a snake … has begun bringing the foreign harlot among the Jews to make them go whoring after false gods, which is to say, worshiping other gods.” " Feiner (Kindle Locations 170-171).

His fans and opponents alike intensified his reputation and built it up to mythical proportions. Mendelssohn was portrayed as someone who directly shapes Jewish history – a depiction that was far-fetched. His real influence was of course much more modest.

At the age of 32, in 1761, Mendelssohn asked Rabbi Yonatan Eybeschütz (note 2) for a rabbinic ordination. Rabbi Eybeschütz was deeply impressed by Mendelssohn's erudition and sharpness and compared him to no less than Moshe Rabbeinu! However, despite this admiration, the Rabbi, who had a great influence yet was accused of Sabbateanism, refused to grant him the title of "Rabbi." This was not the first time that Mendelssohn, who broke through the walls of the Orthodox ghetto, paid a heavy price. Despite his impressive halakhic knowledge, the fact that he published his teachings in German on the forums of the German intellectuals marked him as someone who 'crossed the border'. Rabbi Eybeschütz made do with a letter of recommendation that was passionate albeit didn't grant Mendelssohn any rabbinical authority. “It seems that Mendelssohn, in view of his Talmudic erudition, expected Eybeschütz to grant him the rabbinic title Morenu, “our teacher,” or the somewhat inferior Haver, “peer.”” Feiner (Kindle Location 261). In the end, Eybeschütz decided that a letter of recommendation replete with praise would suffice, thus sidestepping formal ordination to the rabbinate. Granting the title of Haver, Rabbi Eybeschütz explained in his rejection, would constitute diminished respect for a Jew of Mendelssohn’s stature; because he was still unmarried, on the other hand, he could not be ordained Moreno, which would enable him to rule on matters of Jewish law. Therefore, Eybeschütz wrote, all he could grant Mendelssohn was his blessing and “a covering of the eyes” (after Genesis, 20:16), a kind of testimonial to his visitor’s legitimacy as a scholar.” Feiner (Kindle Locations 274-280).

A second slap in the face came ten years later, in 1771, from the other side of the divide: Frederick II - the enlightened albeit anti-Semitic ruler, rejected the unprecedented recommendation of the Royal Academy of Sciences to add Mendelssohn as a full member. Mendelssohn responded in a philosophical tone that it is better to receive the academy's approval and not receive the approval of the king than the other way around.

Frumet Guggenheim

A year after his request for rabbinical ordination had been rejected on the pretext that he was single, Mendelssohn got married to Frumet Guggenheim at the age of 33. The Hamburg-born Frumet was eight years younger and a head taller than the groom.

Moses Mendelssohn was also a pioneer in the way he chose his intended future wife, which was completely different from what was accepted in those days. Usually, a match was made by the parents and involved a detailed financial contract. In Mendelssohn's case, the meeting occurred through a mutual acquaintance – Frumet's friend who was also the daughter of the industrialist with whom Mendelssohn worked. From the outset the relationship was based on romantic love. He wrote to his friend Lessing that his intended bride has no property, beauty or education, but he is in love nonetheless. Regarding the happiness that made his head spin he wrote to his friend: "In the last few weeks I have not spoken to any friend, and I have not written to any friends. I have stopped thinking, reading and writing ... I did nothing but make love in celebrations, celebrate and observe sacred customs ... As cold as your friend's, to melt away from emotions, and put thousands of distracting matters into his head "(Feiner, kindle location 887).

|

| |

The visit to Hamburg was short. After they had parted, they continued to cultivate the relationship for a year through dozens of love letters. In the letters that were saved, Mendelssohn expresses longings that No philosophical study has the power to mitigate.

As a member of an upper-middle-class family Frumet was no stranger to high quality education given by private tutors. However, as soon Mendelssohn chose her as his designated wife, he began to interfere in her education. He recommended certain books for her to read and hired a private tutor to teach her French. He encouraged her to expand her knowledge, but only to an extent befitting a philosopher's wife and a hostess in his home, not beyond. Mendelssohn, like other men of his generation, expected his wife to remain within the confines of the domestic space. When he felt she was investing too much time and effort in her studies he was quick to throw cold water on her enthusiasm: "What do you expect to gain from this? To become a 'scholar'? May god save you from that!" This clear gender-related division between female and male roles and the exclusion of the female from the scholarly world emerges clearly even from the earliest portraits of the couple that were preserved.

The union between the couple was delayed for a long time due to difficulties in obtaining a residence permit for Frumet. When the special permit was finally obtained and they were married, their legal and civil status was still inferior and problematic. When Frumet became pregnant, Mendelssohn sought to upgrade his status to that of "protégé" and thereby to provide his young family with relative security. He swallowed his pride and turned to Frederick II, who was responsible for the civil oppression of the Jews, for permission to obtain the permit. Friedrich, who was considered enlightened and was a friend of the greatest philosophers of the time, was also an anti-Semite. He had ignored the request until the Marquis de Argen sent him Mendelssohn's personal letter with the comment: "A philosopher who is a bad Catholic (de Argen) asks a philosopher that is a bad Protestant (Friedrich) a privilege for a philosopher who is a bad Jew (Mendelssohn) " (Feiner, kindle location 992).

Mendelssohn's success as a philosopher made it difficult to ignore his request and he became an "extraordinary Jew of protection."

Throughout their life Mendelssohn and his wife led an Orthodox religious life-style. Mendelssohn bragged to all his friends that he had a "woman from the heavens” who wore a head cover, kept the Jewish holidays and cooked only kosher food. In the eighteenth century the European bourgeoisie had a sense of family intimacy and the bond between parents and their children grew stronger. The couple invested heavily in educating their children, nurturing them lovingly, traveling and spending time with them. Unfortunately, this familial harmony was damaged by the deaths of four of their ten children. The grief caused Mendelssohn to delve into the meaning of life and death:

"Was it possible that man was ephemeral?" Mendelssohn was certain that it was not: "I cannot believe that God has set us on his earth like the foam on the wave", and he found consolation in that thought. From that moment the question of the immortality of the soul became an urgent existential issue, not only a philosophical and religious problem, and he continued with his attempts to find logical proof "(Feiner, kindle location1012 ).

The book was highly successful and established Mendelssohn's status as a recognized philosopher. In an age of rational thinking, it was difficult for the newly educated and learned to give up the consolations offered by religion, namely, the promise of the soul's survival after death and the hope for the goodness of paradise. Mendelssohn, who knew how to synthesize the two world-views, presented in his book a way to engage in rational and enlightened thought without giving up the solaces offered by a naive faith in the afterlife.

The Mendelssohns' religious way of life did not come at the expense of a bourgeois European lifestyle. The family's economic situation improved over the years and Mendelssohn, who had told his wife at the beginning of their acquaintance that he despised the company of rich Jews, now had many social relations with them, and later also associations through marital ties.

Mendelssohn's public status grew beyond the framework of Jewish society. The culmination was an invitation he received in 1771 to the palace of Frederick II in San Susi.

The family enjoyed the diverse cultural atmosphere that Berlin offered. Their living room became a pilgrimage site for family members and Christian and Jewish friends. Mendelssohn, who loved music, made sure his children received a good musical education and even learned to play the piano himself. Solomon Maimon, a young Jew from Lithuania who emigrated to Berlin and became a famous philosopher, told in his autobiography that when he opened the door to Mendelssohn's house he felt himself in foreign territory and fled the elegant place and its respectable crowd.

The Enlightened: "The Berlin Bubble"

Mendelssohn was the first Jew to break the walls that isolated the Jewish public. In other words, his connections with various figures of the Enlightenment weren't only theoretical but also personal. He developed true friendships outside Jewish Society, whereas in Jewish society itself he often felt intellectually isolated.

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, the son of a Lutheran preacher, became Mendelssohn's soul mate and their friendship lasted throughout their lives. The historian Michael Meyer writes about Lessing: “One of the most prominent representatives of the German Enlightenment who discovered, from his youth, an independent and unconventional spirit. As the son of a Lutheran preacher in a small town, he refused to accept his father's orthodoxy in an uncritical manner. He enjoyed the company of actors and comedians, despite his parents' disapproval of those associations. In 1749 He wrote to his father: 'As long as I do not see that one of the main tenets of Christianity, namely, to love your hater, is better fulfilled, I doubt whether those who present themselves as Christians are indeed such.' " (Meir, p. 18).

They had met for the first time in 1753 in one of Berlin's scholars club and began playing chess and discussing philosophical issues. Lessing, who was deeply impressed by the young man who came from a background completely different than his, introduced Mendelssohn to his friends, including mathematicians, medical physicians and members of the Royal Academy of Sciences. These were friendships that deviated from the intellectual realm and became warm personal ties.

Mendelssohn's new friends were stunned by the depth and profundity of the knowledge exhibited by the "wonder boy" who emerged from an unfamiliar and "exotic" environment. In one of the meetings, he publicly read his work "Thoughts on Probability" and at first no one recognized the identity of the author. It was only when the announcer had made a mistake and Mendelssohn had corrected him loudly that his identity was revealed to the astonishment of those present. Michael Meir wrote about his new status: "His circle of friends and acquaintances expanded as a result of the spread of the" Jewish sage" outside the Berlin border. Guests in the Prussian capital sought his closeness so that he could write down a few wise words in their autographed books. They were eager to meet him and talk to him, to look at this wonderful phenomenon face to face." (Meir, p. 19).

Lessing encouraged him to create, write, and even helped him to print his writings. Elon writes that after Lessing had given him the book of an English philosopher Mendelssohn thought that the essay was good but that he could write something of equal value. Lessing encouraged him to try. Mendelssohn wrote the "philosophical dialogues" and when he later asked for Lessing's opinion, the latter surprised him by submitting him a printed and bound copy of the book. Inspired by his acquaintance with Mendelssohn and with other Jewish friends, Lessing wrote the play "The Jews" in which Jews were shown in a positive light for the first time. Expectedly, such a "subversive" message received scorn from those who lived outside the Berlin bubble. Lessing was accused of writing a 'fictional' play because, as everyone knows, good and positive Jews are nowhere to be found. This event taught Mendelssohn a first and painful lesson. He discovered that his new friends represented the opinions of only a minority of intellectuals.

Mendelssohn stood up to defend his fellow Jews and demanded that the values of humanism and reason be applied to them as well. Despite the self-confidence he exhibited, he was deeply insulted. Feiner writes: "Mendelssohn adopted a tone of self-assurance but also revealed a powerful sense of humiliation. Reading it gives us a first look under the skin of this man of twenty-five years as he realizes to his consternation that the reception that he had been given by Lessing and his friends in Berlin was still far from common. Painfully, Mendelssohn wrote: 'Such thoughts make me blush with shame ...What a humiliation for our oppressed nation! What exaggerates contempt! That ordinary Christian people have from time immemorial regarded us as the dregs of nature, as open sores on human society. But from learned people I have always expected more righteous judgment '"(Feiner, kindle location 632). Mendelssohn was sensitive to the underground currents of what he called the "ghosts" of hateful anti-Semitism that was the lot of many educated people, not just the mob. He often despaired of the Sisyphean struggle against anti-Semitism that overcame the Enlightenment's spirits: "In vain reason and humanity raise their voice, because a prejudice who has become old loses its sense of hearing." (Feiner, p. 115).

Lessing was not deterred by the belligerent criticism and wrote another play called "Nathan the Wise", which dealt with the inter-religious conflict in Jerusalem at the end of the Crusader's occupation. In this play, for which a street is named in northern Tel Aviv, the Enlightenment's ideas of inter-religious tolerance and love of the entire human race were put on a pedestal. The Christian monk in the play claims that Christianity is based on Judaism and that Jesus was himself a Jew. The character of the play's protagonist, Nathan the Wise, was inspired by Mendelssohn. In the play, Nathan gives a parable about a father that bequeaths his three sons three rings that symbolize Christianity, Islam and Judaism, and promises the love of the father/ god to those who would wear them with good intent. Following the publication of the play, a campaign of hostile reactions, mainly led by educated Christians with strong religious tendencies, began. The controversy caused Lessing a great deal of distress. He felt isolated and sank into a depression due to the feeling that his persecutors had defeated him.

|

| |

Lessing died in 1781, a year after the play had been published, but his personality continued to preoccupy Mendelssohn, which placed a statue of his head next to the portraits of the greatest philosophers. Upon the completion of his book "Jerusalem" Mendelssohn intended to take time for writing a composition that would describe Lessing, but his intention did not come to fruition. Jacobi, a scholar from the city of Düsseldorf who represented the religious counter-movement to enlightenment, decided to harm the representatives of the "modern Babylon" that he despised. In a book he published, he disclosed that in his conversations with Lessing prior to the latter's death, Lessing told him that he had become a "Spinozist" and in fact an atheist. At the end of the 18th century Spinozism was akin to heresy. Therefore, Jacobi's claim was a serious accusation. Jacobi and his colleagues' discourse about a "Berlin mentality" had a clearly anti-Semitic tone. Proponents of the counter- enlightenment complained about the influence of Mendelssohn and his friends and emphasized that the father of heresy - Spinoza - was a Jew by origin.

Lessing and Mendelssohn alike tried, each in the confines of his own religion, to live in two worlds simultaneously: the world of religion and the world of enlightenment. The revelation that the late Lessing was actually a "closet atheist" shook Mendelssohn's world to the core. He knew that Jacobi had not lied and wondered why Lessing hadn't confided in him during his lifetime. After deliberation he decided to defend his dead friend's reputation and clarify his motives.

In the last three months of his life, Mendelssohn devoted himself solely to this subject. He wrote a letter to his friend, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which he wondered about the motives of Jacoby who had betrayed his dead friend, revealed the secret of his "heresy" and stained his reputation while he was powerless to defend himself. Mendelssohn wondered whether this act of betrayal was motivated by a Christian missionary impulse designed to harm Lessing and himself, to portray them as heretics and finally, to push him (Mendelssohn) to convert.

Mendelssohn wrote in his book “Morning hours” on religious faith and philosophical thought: "In the book dedicated, as stated, to prove the existence of God were marked two enemies of the rationalist philosophy of the Enlightenment standing on both poles of the reference to God: The materialists who utterly deny the feasibility of an invisible entity, and the enthusiastic mystics, including the Kabbalists, who seek from an extreme religious stature to reach an unmediated encounter with God. The distance between superstitions and hallucinations of religious fanatics and those who deny the existence of God, Mendelssohn thought, is very small. Only philosophizing is the proper weapon to fight these ghosts. "(Feiner, p. 159).

Mendelssohn ran a race against the clock and managed to finish the writing of the "Defense" on December 30, 1785. Upon the end of the Sabbath he rushed outside in the wee hours of the night and in the freezing cold, despite his wife's warnings, to hand over the manuscript to a publisher. He felt relieved that he had accomplished the task. Unfortunately, soon thereafter he died of an illness. Soon after Mendelssohn passed way, his friends blamed Lessing's detractors for his premature death. Mendelssohn's portrayal as a saint who sacrificed his life to protect reason and enlightenment against fanaticism, superstition and religious zealotry- intensified the myth surrounding his image.

His writings

'Ecclesiastes Ethics': A weekly in Hebrew printed in 1755 by Mendelssohn and his Berlin friends. The weekly failed and ceased to appear after the printing of only two pages. This modest, short publication, despite its failure, was an important milestone in the history of Jewish thought. It was the first time that a person who had no rabbinical authority allowed himself to "preach morality," and with a tone substantially different from the gloomy frightening pathos of halakhic preachers. In a weekly devoted to the learned-Hebrew -reading public, a call was made for the love of life, nature and man. Years later, in 1782, intellectuals who would see themselves as Mendelssohn's successors would publish the" Measef" that would succeed.

On Mendelssohn's attitude toward the Hebrew, Yiddish and German languages, the historian Haim Shoham writes: "The attack of educated Jews on Yiddish was guided by the belief that language has the power to correct human thought and man's spiritual and cultural world." In his famous letter to Klein (August 29, 1782) Mendelssohn wrote that the Jewish language separates the Jew from the general world and should be seen as a stumbling block to the Enlightenment: "Pure German or pure Hebrew, and even one alongside the other, but not a mixture of both." (Shoham, p. 22).

In addition to Hebrew and German, Mendelssohn also studied French, English, Latin and classical Greek. He used his linguistic knowledge to translate books by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Plato and others into German. For about six years - beginning in 1765, he published about 120 articles.

His book "Phaedon", which was written as an attempt to deal with the grief over the death of his children and with the question of the survival of the soul, became a bestseller and was translated into a variety of languages. It also consolidated his status and justified the nickname he received: "The German Socrates." The book was a song of praise for man and his place in nature. In dealing with the grief over the death of his children, he developed the theme of the soul's survival after death and the comforting faith in the afterlife. Through this work many educated people, Christians and Jews alike, found a synthesis between a rational world view and the comforting faith in the afterlife and paradise.

One of Mendelssohn's most important works, The Annotation, is a German translation and interpretation of the Five Books of Moses. It was written as part of the education of his son Joseph, an educated young man who served as a private tutor for children. Joseph persuaded his father to publish and print the domestic initiative of writing the German translation in Hebrew letters.

This project, which began without prior planning, was a lever for a fundamental change in Jewish culture. Although Mendelssohn generally shied away from far-reaching innovations, this project was an exception. \

unsurprisingly, it aroused fear and opposition among the rabbis, who mainly feared the shift of emphasis it entailed from Talmudic studies to Bible studies. It also challenged the halakhic establishment with its focus on the Hebrew and German languages at the expense of Yiddish, the establishment's main language.

Elon writes that in Mendelssohn's opinion "many psalms and biblical texts were excellent examples of lyric poetry of the Hebrews, whose clear meaning was blurred too long by mystical interpretations of the Bible. He aspired to renew Hebrew poetry in philosophy and biblical interpretation areas that had already broken out among German Jews. In many ways he wanted it. And his initiative for the revival of Hebrew poetry and literature in the nineteenth century, the so-called Hebrew Enlightenment, which saw the Bible as a literary gem" (Elon, p. 55).

The rabbis gave Mendelssohn a pass with regards to his flirtation with Christian intellectuals, which they nevertheless found contemptuous, but they were not as tolerant when they felt that he had invaded the religious territories they considered their own. They named his approach "the Berlin religion", began talking about a boycott, and the rabbi of Hamburg issued a threat, according to which whoever read the translated Pentateuch would be banned. Funding for the project was made possible thanks to an 18th century version of mass funding. Educators and young businessmen signed in advance on subscriptions in dozens of communities in Western and Eastern Europe. The opposition of several rabbis and threats of boycott were overcome by the signing of powerful figures like the king of Denmark and heir to the throne. Consequently, the rabbis refrained from imposing a boycott. They didn't want to be perceived as challenging the authorities.

Three years before his death, he had completed his most important and influential work, "Jerusalem," which was the only book that earned him a respectable amount of money. In this book, he fought with the "enlightened" who urged him to complete the process of progress and convert to Christianity. In addition, he defended the principles of Judaism. On the other hand, he also fought against the intellectual rigidity and close mindedness of the Jewish orthodoxy.

His latest book, "Moadi Shahar - Morning Hours", is the fruit of joint studies with young people (Including his son Joseph and his son-in-law Shimon Piet) conducted in the early hours of the morning, at a time when his health still allowed it. The aim of these studied was to protect the young generation from the dangers of assimilation and loss of faith in God.

After Mendelssohn's death, four of his six children converted to Christianity. Dorothea (formerly Braindel) abandoned her husband Shimon Piet, married a well-known German writer and even converted to Christianity. Dorothea and Shimon's sun, who also converted to Christianity, became a well-known painter who drew, among other things, paintings riddled with religious motifs. At the time of writing "Moadi Shahar " Mendelssohn's main interest was to defend the reputation of his friend Lessing and the book was a philosophical attempt to do so.

Life on the Seam Line: Confrontations with missionaries, liberals and rabbis

On the complex reality of Mendelssohn's life, Michael Meir wrote: "He mercilessly accepted the restrictions imposed on him by his being observant and faithful to tradition, but he was determined to be German as well - at a time when the concept of German national culture was still a vision in the consciousness of the people. What could have been more ironic than seeing the young and bearded Moshe, who at the time was only tolerated in Berlin, courageously criticizing Frederick the Great for writing poetry in French instead of in German? " (Meir, p. 24).

Mendelssohn's life was therefore fraught with fierce confrontations on inter-religious issues. He described himself as a "non-political type" who wants to devote himself solely to the spirit: "Anyone who dares to innovate should courageously carry it out, bear the consequences patiently, increase his courage, and prefer to go out of his mind, so long as he does not assume that he will be silenced ... My temperament is not suitable for innovations." (Meir, p. 45).

Despite his attempts to confine himself to the realm of philosophy, he was time and again dragged, against his will, into heated arguments about religion.

The Lavater Affair

The most traumatic confrontation occurred when Johann Kaspar Lavater, a well-educated Swiss theologian who was Mendelssohn's friend, called him to convert to Christianity. Lavater betrayed Mendelssohn's trust by publishing statements that Mendelssohn uttered in private. In those statements Mendelssohn said that he respects the moral character of Jesus. Mendelssohn, as many educated Jews, viewed Jesus as a critical Jewish rabbi who never thought of himself as God's son, and never turned his back to his Jewish origins. Lavater who also specialized in a pseudo-science called physiognomy (reading the nature and future of a man according to the structure of his face), presented a sort of public ultimatum when he demanded from Mendelssohn to explain why he rejects the principles of Christianity and refuses to convert. For Mendelssohn, this event marked a serious personal injury and proof that even in the so-called "enlightened" community, he is not really treated as equal among equals, at least not as long as he retains his Jewish belief. He tried, with all his might, to avoid arguments about religion. He was also angry at his friend - the editor of Lavatar's book, but when the latter renounced Lavater's move, Mendelssohn wrote to him: "Let us embrace each other in our thoughts! What we have been given, then we are both human beings" (Meir, p. 36).

|

| |

Lavater must have been aware of Mendelssohn's precarious status as someone devoid of rights. He must have also been aware that any justification that Mendelssohn would provide for his unwillingness to convert might be interpreted as an attack on the ruling religion. Mendelssohn replied to Lavater in a long and reasoned public letter, and the argument between them was the talk of the day, with every sentence and letter from each of the interlocutors receiving record circulation. In the end, Lavater apologized for demanding Mendelssohn to justify his religious belief and convert to Christianity.

Confrontations with the rabbinical establishment

Mendelssohn generally maintained good relations with members of the Jewish community, even though the rabbis were furious at the right he had taken to preach morality, guide and try to influence public opinion. They saw this as a dangerous invasion into a territory they considered theirs and theirs alone. But Mendelssohn always managed to cool the flames. The fact that he maintained a strictly Orthodox and observant lifestyle helped him. For example, despite his long and courageous friendship with Lessing, he never drank wine that his friend poured because of the halakhic commandment that one should not drink wine that was poured by a non-Jew.

Various communities, some distant, appealed to him to exert his influence and use his fluent style in German to help them with the authorities. As a token of appreciation for his efforts, he was exempted from paying the community tax in Berlin, a symbolic privilege granted only to halakhic authorities. Despite the appearance of a respectable relationship -Mendelssohn was generally critical of his friends from the rabbinic establishment due to what he considered as their rigidity, superstitions, narrow-minded education and intolerance. In a private letter to his wife, written in Poland where Orthodoxy ruled, he expressed his true feelings: "Praise be to God that we have left the borders of Poland. This is a country where Tisha Be'Av is a good day. Here they do not worry about anything other than the superstition and the wine of the resin. "(Feiner, p. 96)

"Words of Peace and Truth" by Naphtali Hirz Wessely

Historians define Mendelssohn as a figure of "the early Enlightenment" and his successors, those who saw him as their teacher, as members of the Enlightenment itself. In the days between the two stages, significant changes took place in Europe regarding the Jews and their status. In January 1782 Emperor Josef II ruled over the Austro-Hungarian Empire and published the first "Letter of Tolerance" which constituted a real revolution. A great influence on Jewish public discourse was exerted by the scholar Dohm, who wrote a book on ways of integrating the Jews into the general society and turning them into ordinary citizens. The book was written at Mendelssohn's request following the call of the Alsace's Jews. The winds of freedom and equality that heralded the imminent arrival of the French Revolution contributed to the feeling that this is a time of tremendous change.

In the "The Book of Tolerance" Naphtali Hirtz Wessely, an intellectual from Mendelssohn's circle of friends, published his letter "Words of Peace and Truth" and aroused a storm in the Jewish world. Wessely saw the Emperor's orders of tolerance as a rare window of opportunity and appealed to the Jews not to miss the chance by remaining passive. He called upon them to voluntarily establish a system of modern Jewish schools in which halakhic studies will be combined with so called "core subjects." The rabbis viewed this call as an existential threat, and in the battle for control and hegemony all means were legitimate. Wessely's books were burned, threats were made against him, and the Chief Rabbi of Berlin was pressured to expel him.

Mendelssohn's confrontation with the Christian world was divided into two categories: On the one hand, confrontations with religious missionaries who tried to convert him. On the other hand, encounters with liberals who claimed that the Jewish religion was dark and oppressive and therefore Mendelssohn, as a philosopher and intellectual, should renounce it. Now it was the liberal public that followed the persecution campaign against Wessely with interest. They saw this as proof that Jewish society had failed in the test of enlightenment, was not ripe for integration into civil society, and therefore, that Jews should not be granted full rights.

Mendelssohn, who fought all his life to apply the values of freedom and tolerance that had begun to flourish in Western Europe to the Jews as well, felt that his position suffered a defeat in the public opinion. He therefore acted behind the scenes energetically against the persecution. He tried to prove that Wessely's persecutors were an insignificant minority, and in his efforts even appealed to the rabbis of Italy, who were known to be more liberal, to support Wessely and minimize the damage done to the Jewish cause.

Epilogue

The difficult confrontations into which Mendelssohn was dragged against his will harmed his health. On the advice of his doctors, he was forced to abstain from learning and human company. In the summer of 1785, at the age of 56, his friends came to celebrate his birthday and subsequently his feeling improved. He felt protected and loved as he was surrounded by his family and friends, who shared his love for knowledge, curiosity and the values of the enlightenment. He finally sensed that his pains were alleviated and wrote to his friend that better company could not be found in all of Germany. However, at the end of that year he had hurried on a cold winter night to hand over the manuscript that constituted his defense on his friend Lessing, and two days later he died due to a complication of a cold. The funeral and obituaries reflected the great appreciation he received among Jews and Christians who believed in his path.

Mendelssohn didn't foresee the horrors of the holocaust. Nor could he imagine present day vibrant Berlin. Yet, he was not blind to the power of the reactionary forces, as can be seen from a letter he wrote in 1784: "We dreamed of nothing but the Enlightenment and believed that the light of reason would so radiate the environment that delirium and fanaticism would become invisible. But as we can see from the other side of the horizon, it is already rising again tonight with all its ghosts. The most frightening of all is that evil is so active and influential. The delirium and the zealous fanaticism make reason settle for words. "(Feiner p. 50).

His Family

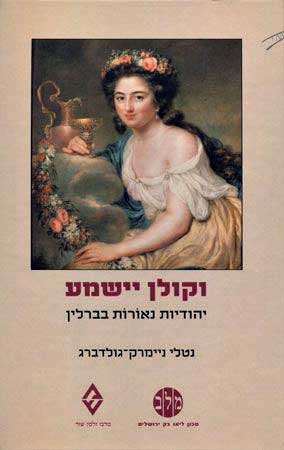

In her book "In the Enchanted Circle - Jews, anti-Semites and other Germans" Prof. Shulamit Volkov drew the attention to the correlation between the promotion of the Jew's civil equality and the bestowal of rights to them, and the acceleration of the self-same processes with regards to women. Frumet Mendelssohn belonged to the middle generation of Jewish women. In her youth, she acquired a certain level education, but settled for her role as a hostess concerned with the welfare of her guests. Moses Mendelssohn invested heavily in educating his children and brought them excellent teachers. Gender discrimination was restricted to Torah studies. In this field the girls Rachel, Brandl, and Wintel did not learn what the brothers learned. However, the girls received excellent education in the other fields. The Jewish girls of Berlin broke through the walls of their parents' generation. Many of them founded Salons in their spacious apartments where they hosted members of Germany's intellectual and artistic elite. They corresponded with each other and with intellectuals and writers of high stature like Goethe, who consulted with his Jewish friend about literary matters. Fanny Mendelssohn - granddaughter of Moshe Mendelssohn, was one of the first known female composers.

|

| |

These salons, which were concentrated mainly in the Unter den Linden boulevard (under the pine trees), are of interest to this day, and many books have been written about them and their heroines, including Mendelssohn's daughters. The creation of these salons required a lot of courage from women whose civil status was inferior and who risked deportation because they challenged the existing gender hierarchy. In France, women's presence was accepted in literary salons but in Prussia women were excluded. The salons became subversive places where men and women met, as well as people from different parts of society who were unlikely to engage in dialogue elsewhere. "During her visit to Berlin, the famous French writer Madam de Staal noticed that Jewish salons were the only places in Germany where aristocrats and bourgeoisie met freely and were not stinking of beer or smoking." (Elon, p. 73

Prof. Zohar Shavit wrote about the strong Jewish women of Berlin in an article published in Ha'aretz on September 18, "Each of the women had a fascinating biography of her own, but their life stories also shared some common features: they belonged to wealthy families who provided them with the type of education that was common among the German bourgeoisie, namely, private education at home that included, among other things, the study of foreign languages. They mastered German and French, and sometimes Latin, English, and even Greek and Danish. They married within a narrow circle of the high Jewish bourgeois families. However, but most of them divorced their Jewish spouses at a relatively early stage in their lives, converted to Christianity before or after marrying a non-Jewish spouse, and took lovers which were usually non-Jews that belonged to the nobility.

Jews were members of the nobility. More than anything else, they shared the lust for knowledge with each other and embodied and fulfilled Kant's call, "dare to know," and did so with determination, feverishness, and total dedication, as if they wished to overcome a centuries-old lack of access to education. They read, one might almost say, devoured, the typical products of the Enlightenment-books, articles, pamphlets, and more. At the same time, music, theater, and the fine arts were not denied. From a historical perspective, their lives can be described as a bold pioneering attempt to change the exclusive presence of men (including educated Jews) in the Jewish intellectual public sphere in Germany and the absence of women from it. Their lives were motivated by a secular worldview and by the willingness to break the shackles of tradition and to escape the restrictions imposed by the accepted norms regarding the status of women and their role in the family structure. "

The intellectual freedom of these woman was unsurprisingly criticized by the rabbinic establishment. But it was also attacked by allegedly enlightened historians. In his book ''History of the Jews" the historian Heinrich Graetz, on whose name a street in northern Tel-Aviv is called, claimed that these young women brought about moral corruption and compared them to the prostitutes of Medyan.

The conversion of many of these women, including Mendelssohn's daughters, was not prompted by a Christian religious impulse, but rather by a desire to liberate themselves from the suffocation of traditional Jewish society. The conversion freed them from the community. Most of them therefore acted out of a completely secular orientation. Opponents of Mendelssohn's Enlightenment-based path resort to the fact that only two of his six children and only one of his nine grandsons remained Jewish, as proof that his path was wrong.

Bibliography

Author (s): Shmuel Feiner

Title: Moshe Mendelssohn

Publisher: Yale University Press

Year of Publication:2010

Amazon Kindle Edition

Shortcut: Feiner

Author (s): Shmuel Feiner

Title: Moshe Mendelssohn

Publisher: Yale University Press

Year of Publication:2010

Amazon Hardcover

Shortcut: Feiner

Author (s): Michael Meyer

Title: The Emergence of the Modern Jew: Jewish Identity and European Culture in Germany, 1824-1749

Place of Publication: Jerusalem

Publication name: Carmel

Year of Publication: 1990/91

Shortcut: Meir

Author: Amos Elon

Title: German Requiem - Jews in Germany before Hitler 1933-1974

Publisher: Kinneret, Zmora, Bitan Dvir - Publishers

Year of Publication: 2004

Shortcut: Ayalon

Notebook: Shulamit Volkov

Name of book: In the enchanted circle - Jews, anti-Semites and other Germans

Afekim Library - Am Oved Publishing

Tel Aviv University

Shortcut: Volkov

Author (s): Haim Shoham

Title: In the shadow of Berlin's education

Place of Publication: Raanana

Publisher: Hakibbutz Hameuhad, Tel Aviv University. The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics

Year of Publication:

Shortcut: Shoham

(1) An article by Prof. Zohar Shavit published in Ha'aretz on 18.9.2013 "The first to dare to know."

http://www.haaretz.com/literature/study/.premium-1.2118592

Remarks:

Note 1: See Kobi Ariel's comments on the image of "Moishe Medsoy" in ultra-Orthodox society at 1.06.

Below is a link to the educational television program 7https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNVNoKEbv7M).

Note 2: Named after him a street in northern Tel Aviv, adjacent to the street after his sworn enemy Rabbi Amidin.

On the Emden-Eibschutz Debate: A Lecture by Yehuda Liebes, The National Library of Jerusalem,

On November 11,

pluto.huji.ac.il/~liebes/zohar/pulmusemden.docx

For further information:

Between Judaism and Germanism - Interview with Prof. Moshe Zimmerman

Merav Geno, Assaf Tal and Bilha Shilo at Yad Vashem.

http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/education/interviews/moshe_zimmermann.asp